This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

History of Banking: From Goldsmiths to Today’s Financial Systems

Human innovation has seen the rise and fall of major global industries. Since the Industrial Revolution kicked off in 1760, the world has witnessed textiles, railroads, and oil production boom to become the largest and most influential industries. These industries, as we know them today, are a long way from their peak of global influence. In the early 21st century, technology has arisen to give us 8 of the 10 most valuable companies in the world. Throughout these ebbs and flows in global industries, there has always been a constant: global banking.

Banking has been there to accommodate and steer this progress, remaining relevant as other businesses fade into obscurity. The world of banking is as hated as it is misunderstood. More often than not, attempts to explain how banking works quickly devolve into wild conspiracies. Tensions arising from ever-increasing debt levels have caused many people to point the finger at these institutions—institutions that only seem to get richer as the world becomes more unstable. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis was kicked off by major structural issues in the global banking system and exacerbated by record levels of household debt.

Today, the world is on the brink of yet another major financial downturn, and yet again, household debts are at record levels. So, is banking really to blame? Are the wild conspiracy theories about central banks and soaring national debt true? What role are banks supposed to play in our modern economies? And, more importantly, what role do they actually play?

This episode of Economics Explained was made possible by our fans on Patreon. If you’d like to gain early access to these videos before they’re uploaded to YouTube, as well as participate in exclusive live Q&A sessions, please consider supporting our channel at Patreon.com/EconomicsExplained.

The Humble Beginnings of Banking

Banks weren’t always the silent superpowers they are today. They actually had very humble beginnings. Understanding these origins is instrumental in revealing the most valuable asset a bank has on its books: trust.

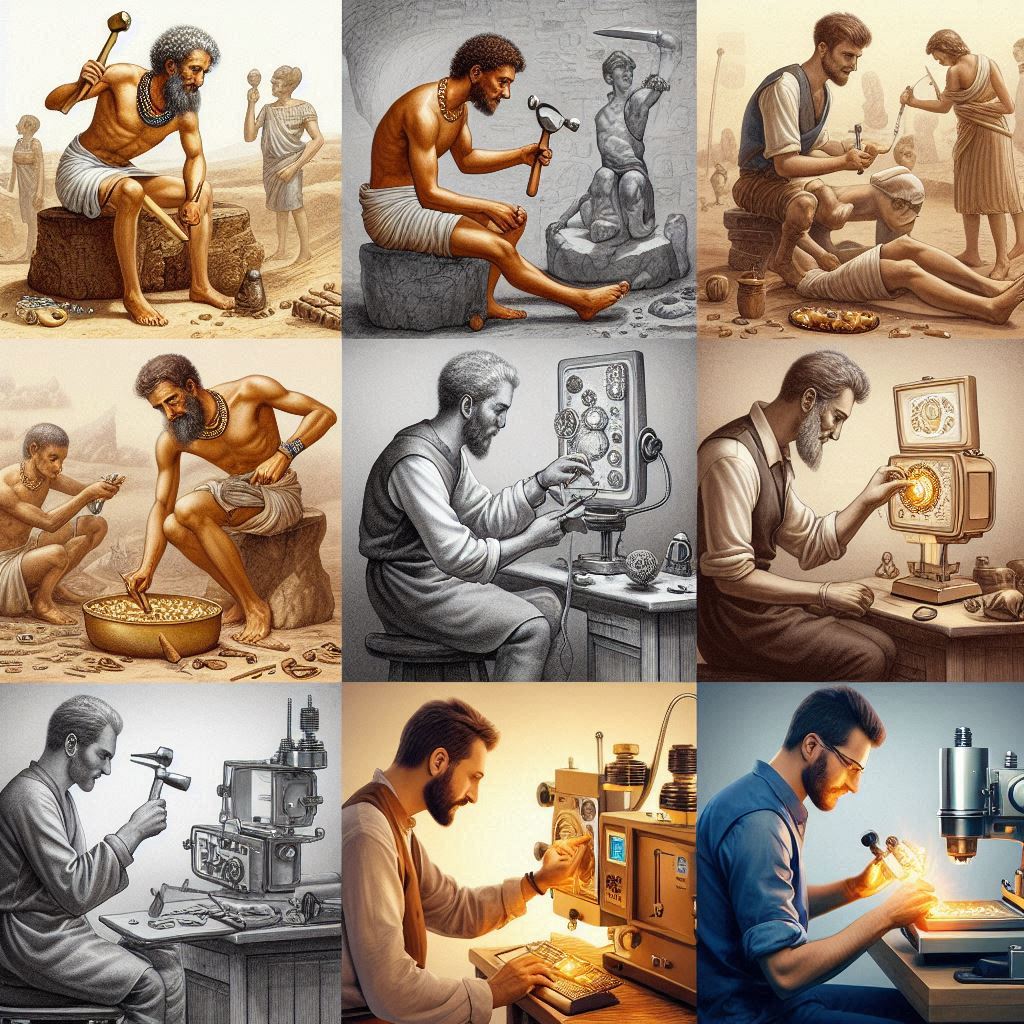

Banking, as we know it today, was forged in the foundries of goldsmiths. These tradesmen would ply their craft at minting, jewelry, and, most importantly, coins. For hundreds of years, gold has been universally accepted as a currency because it is cost-dense, very chemically stable, easy to work with, and limited in supply. Gold became the intermediary for trade, eliminating the need to rely on barter or less-than-ideal currencies.

However, gold by itself is still difficult to trade with. It’s hard to tell if some crafty conman is trying to pass off gold alloys as pure gold, it’s difficult to break up a chunk of gold for a prescribed value, and it’s also risky for an average person to keep too much gold for fear of being robbed.

The Evolution of Goldsmiths

Minting coins was the solution to these problems. By building up a good reputation, goldsmiths could cast gold coins with guaranteed purity and weight. As long as the coins retained the seal of the goldsmith, people could determine their value instantly without having to go through the trouble of weighing and verifying the gold for every transaction.

Of course, people would attempt to forge these coins, which meant there was a constant arms race to make more ornate seals to verify authenticity. This shows that even from its humble beginnings in the workshops of tradesmen, banking was all about the trust people had in the institution.

Of course, this simple arrangement didn’t last forever because of the third problem with gold: it was risky to keep on hand. People trusted goldsmiths to keep their gold because their whole business model relied on their reputation. The goldsmiths’ facilities had to be fortified and protected, given the value of the materials they worked on day in and day out.

For a price, the goldsmiths would store people’s gold in their vaults. This provided another source of income for the goldsmiths and peace of mind for people hoarding their life savings. This is similar to banks today that offer negative interest rates on deposits. It sounds bizarre to pay money to give someone money, but a lot of people are happy to do it just to ensure their wealth is secure.

The Rise of Modern Banking

But for the goldsmith, this humble arrangement did not last forever. Business really took off when the goldsmiths started commodifying trust. In exchange for people’s deposits, goldsmiths would write receipts detailing the amount of gold on deposit and where the bearer of this receipt could pick this gold up from. People would again try to forge these receipts, so the goldsmiths had to put a lot of effort into making these receipts just as ornate as the coins they minted.

It’s a common misconception that goldsmiths started making their fortunes by lending out their depositors’ gold directly. This certainly happened, but in reality, there was a far more lucrative way for them to commodify their trust.

The Birth of Banknotes

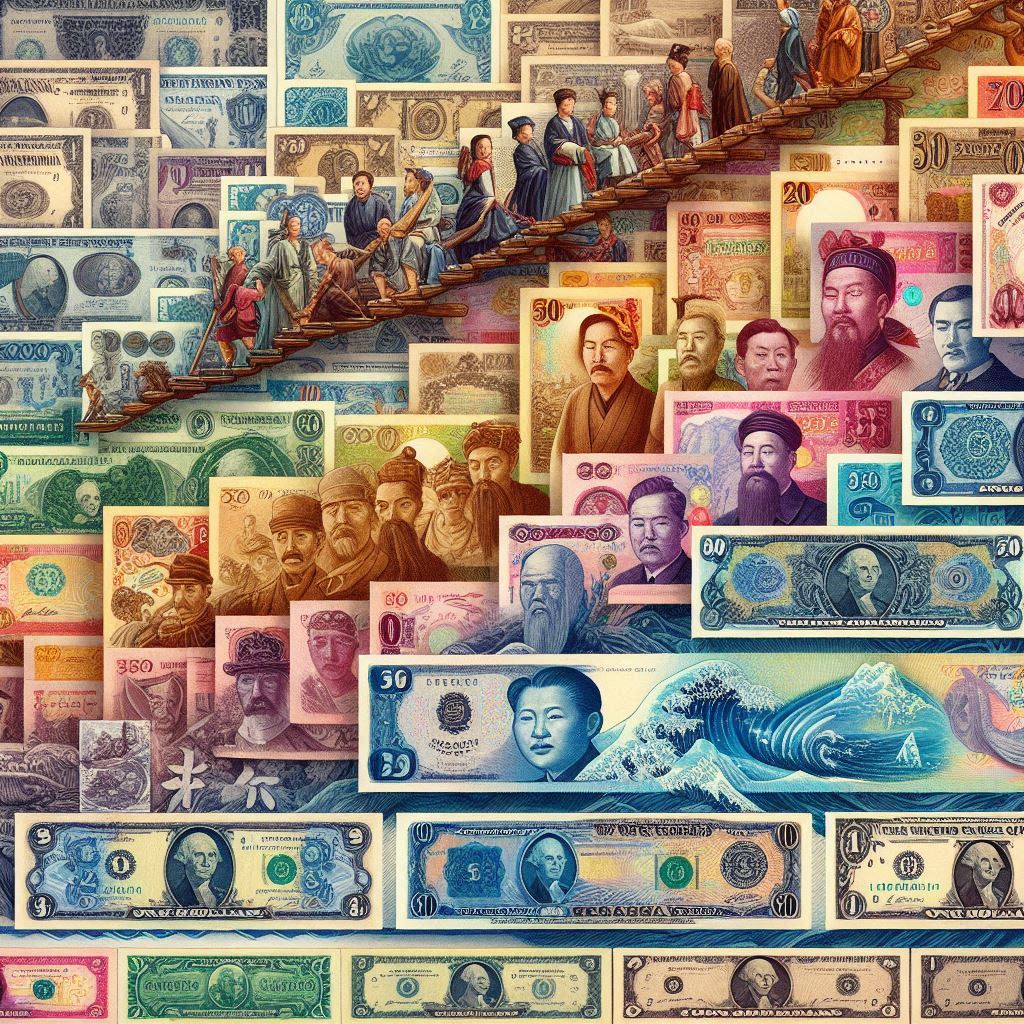

The deposit receipts goldsmiths gave out started to be used for trade directly. People found it much easier to carry around these receipts than gold coins because they were less heavy and could reflect a larger value than what was reasonable to carry around in a coin pouch. This was the origin of modern-day banknotes, where even today, the paper rectangles represent a higher value than the metal coins. The respect the public gave these deposit receipts was the turning point that kicked off modern banking.

Now, if a goldsmith wanted to loan money, they did not need to give out their own gold or even their depositors’ gold. They could just write out these receipts. People understood that these receipts were exchangeable for their nominated value in gold, so they continued to trade with them, knowing they were as good as gold. What this let goldsmiths do was write more loans than what they actually had in gold.

If a goldsmith personally had one ton worth of gold and was keeping nine tons of other people’s gold, he would have a total of ten tons of gold in his vault. In this reality, there would be deposit receipts for nine tons of gold out there in the economy being used for trade, which at any point could be exchanged back for real physical gold.

The Dangers of Over-Leveraging

Although there was nothing stopping a crafty goldsmith from just loaning out more of these receipts when people asked him for a loan, the borrower could still use this receipt to make whatever purchase they needed to.

The goldsmith got to collect interest on gold that never existed, and the people holding onto these deposit receipts still believed they could all be handed back in for cash. It was a win-win all around, or at least it would be until too many people came back and demanded gold.

If this lending got out of hand, there might be receipts floating around in the economy for 100 tons worth of gold. If even one-tenth of people came in to exchange their receipts for gold, the goldsmith would be completely broke. As soon as one person couldn’t withdraw their gold, the news would spread quickly, and people would swarm through the doors to trade in their receipts for gold that never existed. This whole system relied on people rarely ever withdrawing their money to prevent what came to be known as a bank run.

The Role of Central Banks

Over time, this system became more and more institutionalized. Goldsmiths rebranded to banks and became the go-to place for deposits and lending. Still, the threat of bank runs loomed ever-present. As banks grew in popularity, these institutions started to realize that their own success was determined by their competition. If a single bank experienced a bank run, that panic would spread quickly to other banks’ customers, which would quickly reveal just how exposed they were all along. The banks needed an extra layer of security to ensure that every individual bank would always be able to service its withdrawals. The solution was a central bank.

A central bank is like the bank to other banks. If there was an instance where too many customers withdrew gold from one bank on a given day, the central bank could step in and borrow gold off a bank with plenty in reserve and give it to the bank that needed to satisfy customer withdrawals. By doing this, the banks could pool their collective gold reserves, which meant that it was far less likely any bank would ever be unable to service its withdrawals. This meant it was far less likely to have a run on an individual’s bank, which meant there was never going to be mass panic that took down all banks. Sounds great, but there were a few issues.

The Challenges of Central Banking

For starters, this central bank would need all of the participating banks to use a single universal currency. Before central banks, deposit receipts were unique to every different bank. They had their own designs and were only exchangeable for gold at the particular bank noted on the receipt. Central banks issued their own notes that were to be universally accepted anywhere. This wasn’t the issue; in fact, having one single currency made trade a lot easier. The issue was that if the public lost faith in this currency, the whole system would be made redundant.

All of the nation’s perceived savings would be wiped out, and there would be no backup options like there would be in a system with totally independent banks.

The second and more significant problem was that giving the power to control money to a single institution that was not a government was hugely destabilizing. “Permit me to issue and control the money of a nation, and I care not who makes its laws,” famously explained by Mayer Rothschild, who was one of the most powerful bankers in history. Like a lot of information around central banking, the Rothschilds, and money in general, this quote is actually not true. There is no evidence to suggest that Mayer Rothschild ever said this.

What must be understood about lenders, gold, money, central banks, and the Rothschilds is that they are all very powerful, very complicated, and very opaque—all of which is fertile ground for wild conspiracies.

The Modern Role of Banks

It’s difficult to really understand the role of banking in the modern world without it being described by someone on a soapbox, regurgitating very popular, very entertaining, and very alarmist theories that, for the most part, are simply not true. So, what is the role of modern global banking? A boring middleman. Banks have an important role to play in our economies.

They are known as financial intermediaries. Their function is to facilitate trade through the easy storage and transfer of money. From barter to gold coins to worldwide wire transfers, the ability to reliably pay for goods is a central function of an economy. We owe our quality of life today as much to the financial revolution as we do to the industrial revolution.

The role of an intermediary also extends to allocating capital efficiently. Of course, another major part of a bank’s role is loaning money. In theory, this contributes to economic development by taking idle capital deposits and allocating them towards promising businesses that need the cash to start producing value for society. This role of a financial intermediary is not a glamorous one. There is no reason to expect this industry to be more than what accounting firms are today. Banks provide a service that takes some skill and manpower.

They provide a valuable service and could probably charge a healthy premium for it, but they would still fall far short of the multi-trillion-dollar monolith they are today.

The Shift in Global Finance

So, where has this extra power and influence come from? Professor Richard Werner is an award-winning economist on this issue, and he notes that there is no value added by the financial sector, regardless of what kind of financial products they come up with. But he also offers an explanation as to what their role is in reality. They don’t add value; they make up value.

The 20th century saw a paradigm shift in the role of global banking. The Federal Reserve was formed, and then the Bretton Woods Conference made the United States the de facto financial center of the world. The Bretton Woods Conference is something we have explored before on this channel, but in short, it was a meeting held in July of 1944 that brought together 44 nations and agreed that all currencies would be pegged to the US dollar at a set exchange rate, and in turn, the USD would be pegged to gold. This system worked fine up until the 1970s when the gold standard was slowly abolished in the United States. This now meant that the USD was only worth what someone was willing to trade for it, which sounds bad in theory, but in reality, it gave financial institutions far more flexibility in how they created wealth.

The Modern Banking System

Remember back to the cunning goldsmith that wrote deposit notes for gold that never existed? Well, banks today get to do that on a much larger scale. When you go to the bank and take out a home loan, the bank does not move money around from depositors into a check for a new home. No, they simply enter the loan amount into a new account in the same way that the goldsmith wrote out an unbacked deposit note. The difference today is that these figures in a modern bank account are the store of value.

Dollars aren’t so coveted because they are exchangeable for gold anymore; they are valuable because we are forced to believe they have value. Banks ensure that these dollars have value in two ways: The first is by demanding these dollars back with interest. People can’t pay their home loans with seashells, livestock, or even gold bars. They need to pay it back in USD. This means if people don’t want their home repossessed, they need to get some USD.

The second is by ensuring the government levies taxes in this currency. Federal income taxes were introduced in the same year as the Federal Reserve, and this was no coincidence. Being able to conjure something into existence that has value has made banks modern-day alchemists. And this is what Professor Richard Werner identifies as the turning point in global finance. Banks are no longer intermediaries; they are originators.

The goldsmiths of yesteryear were a bit cheeky in writing loans with deposit receipts for gold that didn’t exist, but what they created were effectively gold derivatives. These notes derived their value from the idea that they were exchangeable for gold. Today, banks write loans with debt agreements and make up the cash. The phrase “all money is created as debt” is thrown around a lot when people try to explain this issue, but that’s not entirely true. Modern debt, in any form, is the equivalent of goldsmiths’ deposit receipts. Debt, in a sense, is a derivative of cash. These debts derive their value from the idea that they are exchangeable for cash.

The Bank Run Problem

This causes the same bank run problem we saw earlier, but not in the way you might expect. Before modern banking, these institutions were afraid that too many people would come back in to exchange their notes for gold. They simply didn’t have enough gold to cover all of the notes. Today, modern banking systems are afraid that too many people will try to pay off their debts. There simply is not enough cash in existence to pay off all of the debt in existence. The Federal Reserve Bank estimates that the M2 money supply (that is all money kept in bank accounts, savings accounts, and in physical cash) is around 18 trillion dollars after a huge spike in early 2020 caused by quantitative easing measures. The national debt is currently sitting at 26.1 trillion dollars.

When the record levels of household debt are added on top of this, the debt level exceeds 40 trillion dollars. This is to say nothing of state and municipal debts. If people tried to pay off all of their debt tomorrow, there just would not be enough cash in existence to make that happen. When it is then remembered that all of this debt is accruing interest, people would be forgiven for feeling a little bit concerned. It starts to look like the entire economy is the equivalent of someone taking out a new credit card to pay off their old credit card, simply waiting for the day this whole thing collapses.

But there is still hope for the system. There is still a better way. Professor Richard Werner notes that the current debt-based monetary system is not inherently bound to fail, like many people would suggest. In fact, the ability for the system to allocate capital and increase people’s willingness to go out and spend is actually a force for good. The system does inherently rely on an ever-increasing debt pool, but that is not bad so long as productive output keeps up with the increase in debt.

If an economy was to grow its output by 3% per year and the debt and money supply was only to grow by 2% per year, this would be perfectly fine. What you would see in this scenario is that things would actually start to get cheaper. If there is 2% more cash in a society, but 3% more goods and services, the businesses providing those goods and services would have to compete more fiercely for a smaller relative supply of cash.

A really important thing to note here is that this only works if output increases, not necessarily GDP. GDP measures the sum total of all transactions in an economy, whereas output measures the total value of all the things created in that economy.

If I make a table and then trade it back and forth 10 times with a friend for $10, I have raised GDP by $100. In this same example, output is still only one table. There are many asset classes that do not contribute to increasing output but do contribute to increasing GDP. Werner argues that major banks have increasingly favored inert asset classes like real estate through mortgages that just sit there and don’t actually make anything. If these speculative asset classes continue to weigh too heavily in an economy, we will eventually get to a tipping point where genuine output can no longer sustain the demands of the debt burden on the economy.